As the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) continues to plague our nation, it has highlighted existing structural inequities. Over the past few weeks, a number of reports, both in mainstream media and among policy analysts, have documented evidence of the disproportionate negative impact of COVID-19 on low-income communities of color.[1] Florida, one of the nation’s most diverse states,[2] and one of just 14 states that have not expanded Medicaid,[3] is uniquely susceptible to health disparities amid the COVID-19 crisis. In our fight against the pandemic, it is imperative that we acknowledge and address our nation’s long-standing inequities and the resultant disparities in order to achieve equity in healthcare access and ultimately, in health outcomes. This brief offers historical context, then presents data that reveal disparities in COVID-19’s early outcomes in Florida, with a focus on South Florida. Lastly, in light of the emerging disparities discussed, this brief presents recommendations, both to address the immediate crisis, and beyond.

A vast body of research has demonstrated the prevalence of disparities in health and health care. Despite their extensive documentation, there is a lack of consensus as to the causes of these disparities.[4] Factors such as race and ethnicity, sex, sexual identity, age, disability status, geographic location, socioeconomic status, and, relatedly, housing, education, and food security, all influence an individual’s health. These factors, known as social determinants of health, greatly influence health outcomes, and in turn, health disparities across groups.[5]

Across the country, states and localities have begun releasing data that reveals the disparate harm of COVID-19, with communities of color and immigrant communities hit hardest. These reports highlight the real effects of race and ethnicity (social constructs, not biologic fact) on the lives and well-being of individuals, including how individuals experience healthcare. A recent Shriver statement on racism and COVID-19 notes, “a legacy of structural racism has resulted in black and brown communities receiving starkly less in terms of quality education, employment, healthcare, housing, and resources, and starkly more in terms of criminalization, environmental toxins, and willful neglect.”[6]

Over a century ago, W. E. B. Du Bois documented the association between societal inequities and health inequities. “The Negro death rate and sickness”, he stated, “are largely matters of [social and economic] condition and not due to racial traits and tendencies.”

Our nation has a long-standing history of discrimination and racism. From slavery all the way through to redlining and mortgage discrimination, people of color have been disproportionately excluded from the wealth and financial well-being afforded to their White counterparts. Over a century ago, W. E. B. Du Bois documented the association between societal inequities and health inequities. “The Negro death rate and sickness”, he stated, “are largely matters of [social and economic] condition and not due to racial traits and tendencies.”[7] Today, Du Bois’ observation still stands true, as communities of color continue to experience higher rates of premature death and chronic disease compared to Whites, due to an interplay of social and economic factors, many grounded in the legacy of institutional racism and discrimination.

In the midst of COVID-19, racial/ethnic disparities have emerged in the form of increased risk of serious illness and death among communities of color.[8] These racial and ethnic disparities result, in part, from higher rates of uninsurance experienced by people of color which impedes access to COVID-19 testing and treatment.[9]

Further, there is a significant relationship between socio-economic status and COVID-related risks. A recent survey found that Latinos in the U.S. are more likely than members of the population overall to view COVID-19 as a major threat to their health and finances.[10] This fear has been vindicated as emerging data show that, compared to the general US population, Latinos are more likely to report that they or someone in their household has experienced a pay cut (40% vs. 27%) or job loss (29% vs. 20%).[11]

Additionally, the measures required to protect against the virus are not equally available to all residents. While public health experts cite social distancing as one of the most effective control measures of disease spread, 24% of Blacks and Hispanics, compared to 16% of Whites, work in industries where telecommuting is impossible; forcing individuals to risk exposure at work, or face loss of income, or job loss if they are unable or unwilling to report to work.[12] Furthermore, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended the wearing of face masks to slow transmission rates, reports have emerged of discrimination against and harassment of people of color wearing masks, creating fear among an already at-risk population.[13]

Further, higher rates of comorbidities among Black communities, when combined with the unresolved legacies of structural racism (e.g. disinvestment in hospitals serving communities of color), contribute to higher rates of severe illness and death from COVID-19. In other words, COVID-19 health outcomes are beginning to mirror the stark disparities of too many other well-documented health outcomes in this country.[14]

As of April 30th, 382,966 Floridians (1.8% of the state population) were tested for COVID-19.15 Of those, 33,690 (8.8%) were found to have the virus.[16] The number of people tested throughout Florida varies widely by county.[17] These disparities appear to reflect discrepancies in wealth by county. Seven of the ten Florida counties with the lowest COVID-19 testing rates per capita have median incomes of less than $40,000 and/or are considered rural, while almost all counties with the highest testing rates had median incomes above $40,000.[18] Testing, in other words, is coming first to counties with higher-income residents, and putting those in lower-income areas at greater risk.

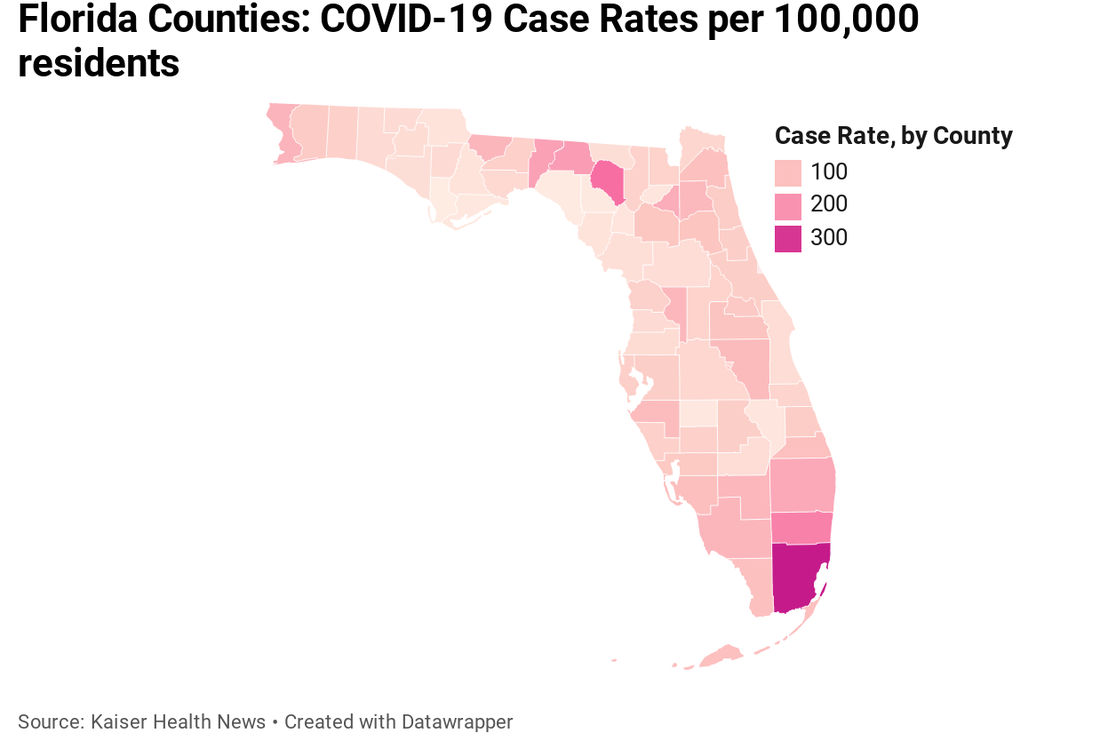

Early data on confirmed cases indicate likely disparities not just in who is getting tested, but also in who is testing positive. Data retrieved from Kaiser Health News shows that South Florida is a “hot spot” for COVID-19 cases with approximately 216 cases per 100,000 residents in Broward County, and approximately 374 cases per 100,000 residents in Miami-Dade County (Figure 1).[19]

Figure 1. Florida Counties: COVID-19 Case Rates per 100,000 Residents

Data by race/ethnicity show that while non-Hispanic Whites comprise more than three-fourths of the state population (54%), they account for just 25% of individuals who tested positive. Meanwhile, Hispanics comprise 29% of those testing positive, and 26% percent of the state population, while Blacks account for 18% of all confirmed cases, and 17% percent of the state population.[20] However, infection rates for Blacks and Hispanics are likely higher than the FL-DOH data reveal as race/ethnicity data is based on self-reporting. Research has shown that Blacks, followed by Hispanics, are most likely to not self-report their race/ethnicities.[21] The DOH data may, accordingly, understate the rates of Blacks and Hispanics with COVID-19.

As compared to the U.S., a greater share of Florida’s population is Black (17% in FL, versus 13% nationwide) and Hispanic (26%, versus 18% nationally).[22] Florida also has higher rates of uninsured (16%) than the nation overall (10%).[23] Given the adverse social determinants of health, high rates of comorbidities, and high uninsurance rates among people of color, Florida, with its diverse population, is acutely vulnerable to health disparities in COVID-19 outcomes.[24]

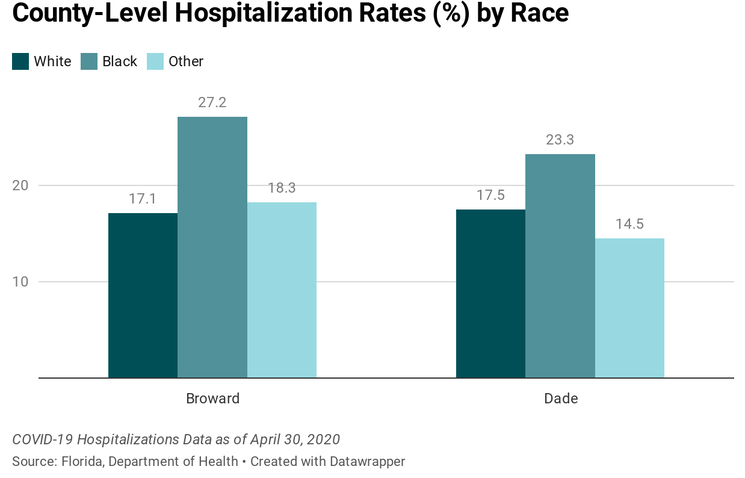

Florida’s COVID-19 hospitalizations data mirror that which is emerging from across the country, revealing the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Blacks. While Blacks comprise just 17% of Florida’s population, and 18% of Florida’s COVID-19 cases, they account for a full 26% of the state’s COVID-19 hospitalizations. Further, a look at the hospitalization data of individuals with a positive test result within race/ethnic groups shows that Blacks with COVID-19 were hospitalized at a higher rate (24.3% of all Blacks with a confirmed case) than that of Non-Hispanic Whites (23.8%) and Hispanics (17.2%).[25]Hispanics, meanwhile, had a statewide hospitalization rate of 17.2%, compared to a rate of 23.8% among Non-Hispanic Whites.[26] This lower hospitalization rate among Hispanics could reflect a relatively lower risk of co-morbidities (such as heart disease and hypertension) among different sub-groups of Hispanics, and/or could indicate that though sick, Hispanics are choosing to avoid hospitals, either because they don’t have health coverage, or because they fear that utilizing public healthcare will adversely impact their immigration status.At the county level, disparities in South Florida are even more striking. Figure 2 shows county-level hospitalization rates by race. In Broward County, Blacks with COVID-19 were hospitalized at a rate of 27.2% compared to individuals classified as “other” (18.3%) and Whites (14.9%). Similarly, in Miami-Dade county, Blacks had the highest rates of hospitalization (23.3%) compared to their White counterparts (17.5%) and those classified as “other” race (14.5%).[27]

In Broward County, Blacks with COVID-19 were hospitalized at a rate of 27.2% compared to individuals classified as “other” (18.3%) and Whites (14.9%). Similarly, in Miami-Dade county, Blacks had the highest rates of hospitalization (23.3%) compared to their White counterparts (17.5%) and those classified as “other” race (14.5%).[27]

Socio-economic factors, as well as differing levels of access to care, likely play a role in these outcomes. The rate of individuals living in poverty is higher in Miami-Dade (16%) than in Broward county (12.6%), and higher than the state-wide rate (13.6%).[28] The proportion of foreign-born individuals is also significantly higher in Miami-Dade and Broward (53.3% and 33.7% respectively),[29] than state-wide (20.5%). Foreign-born residents are more likely to be uninsured,[30] and may be more likely to experience adverse socioeconomic conditions that could increase their risk of severe illness from COVID-19. Further, Black residents of Miami-Dade and Broward likely experience higher rates of uninsurance than Whites, as they do statewide.[31] COVID-19 is almost surely no different than a myriad of other conditions that are characterized by worse outcomes among communities of color and those who lack health insurance.[32] This high rate of uninsured, therefore, may help explain why Blacks in Miami-Dade and Broward are being hospitalized at higher rates than Whites.

Figure 2. COVD-19 Hospitalization Rates by County and Race

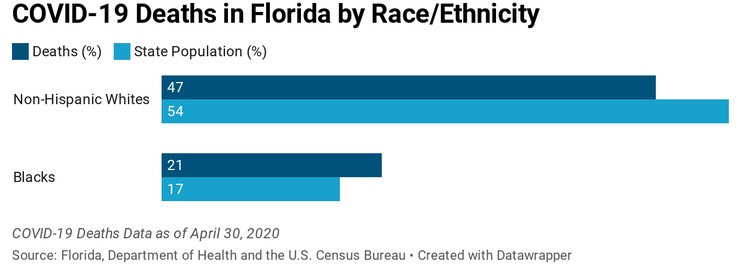

While Blacks account for 17% of Florida’s population, they account for 21% of all COVID-19 deaths statewide. Meanwhile, non-Hispanic Whites, comprising 54% of the population account for 47% of all COVID-19 deaths statewide[33] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. COVID-19 Deaths in Florida by Race/Ethnicity

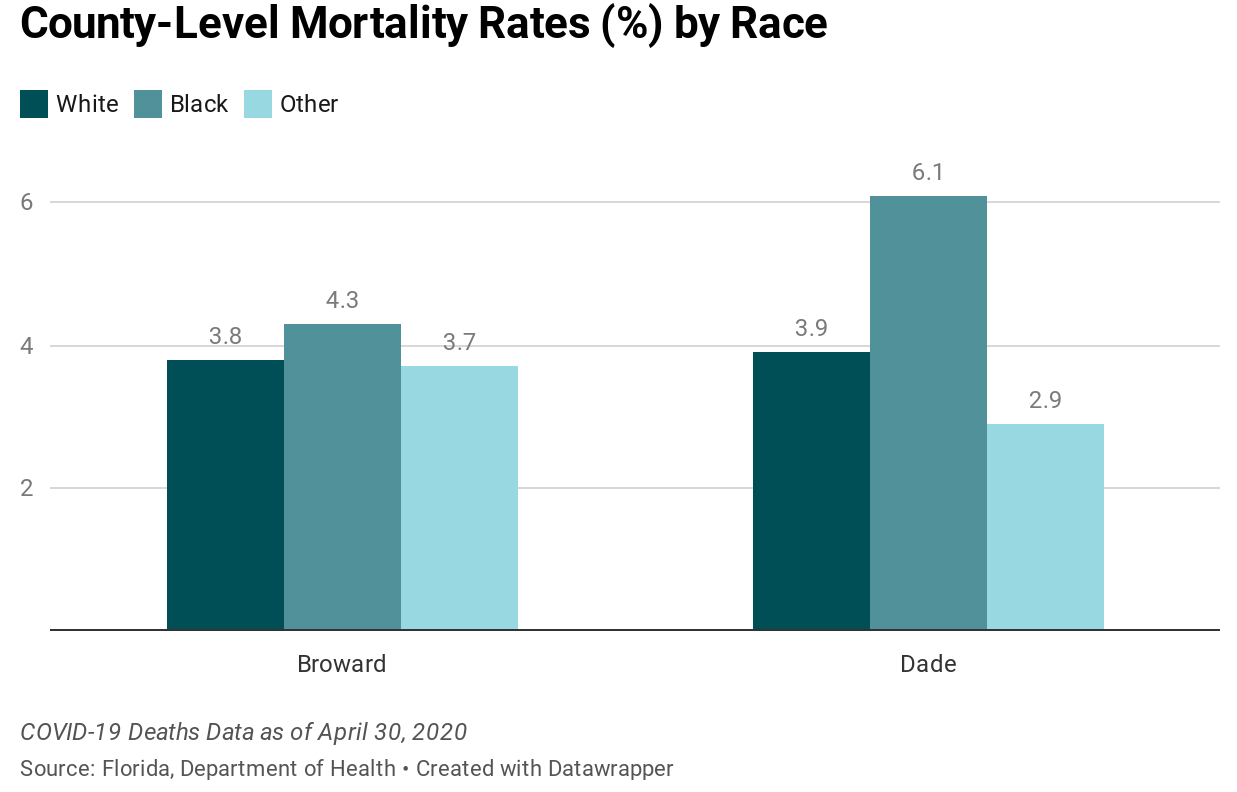

Similar to the hospitalization data, and likely for the reasons discussed above, county-level data for Miami-Dade and Broward counties (Figure 4) indicate that Blacks are disproportionately dying from COVID-19.

Figure 4. COVD-19 Mortality Rates by County and Race

In Miami-Dade County, Blacks with COVID-19 are dying at a rate of 6.1% compared to 3.9% among Whites and 2.9% among individuals classified as “other.” In Broward County, 4.3% of Blacks with COVID-19 are dying, while Whites and individuals classified as “other” are dying at rates of 3.8% and 3.7%, respectively.[34] Again, these disparities are likely explained by the higher rates of uninsured individuals, foreign-born individuals and poverty, and the attendant inability to practice social distancing, within Miami-Dade and Broward counties, factors that present vulnerability in the face of COVID-19.[35]

In Miami-Dade County, Blacks with COVID-19 are dying at a rate of 6.1% compared to 3.9% among Whites and 2.9% among individuals classified as “other.”

Florida’s communities of color are experiencing disparately high rates of severe complications and death associated with COVID-19. In the two counties with the highest number of confirmed cases (Broward and Miami-Dade), Blacks were hospitalized and have died at higher rates compared to all other races; mirroring reports of racial disparities from other states. Florida data further reveal disparities in testing, particularly among rural counties, and those with lower median incomes.

This crisis has underscored the urgent need to combat stigma and discrimination against people of color, in healthcare settings and beyond. An ongoing and multi-pronged approach, inclusive of public education and anti-bias education for healthcare providers and healthcare decision makers will be critical. Expanding Medicaid is key to improving access to healthcare and reducing disparities.

Florida should expand Medicaid, as 36 of our sister states and the District of Columbia have done.[36] Doing so would not only dramatically improve health outcomes, it would also alleviate the cost burden experienced by hospitals treating uninsured patients.[37] In fact, a recent report by The Commonwealth Fund found that expansion states will receive more federal dollars through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) Act compared to non-expansion ($1,755 in federal funding per state resident versus $1198 per state resident).[38] This amounts to billions of federal dollars that Florida could garner to cover the uninsured and mitigate the financial loss that will be experienced by Florida’s healthcare systems amid the COVID-19 crisis.

Short of permanent expansion and to address the immediate crisis, the state should, at a minimum, expand Medicaid temporarily to individuals with COVID-19.[39] Florida should also adopt the state option to provide Medicaid coverage of COVID-19 testing for uninsured residents, and extend emergency Medicaid coverage to individuals with COVID-19 symptoms, regardless of immigration status.[40] In addition to addressing the access barriers impacting health outcomes, Florida should address the social determinants of health that are hastening the spread and worsening the outcomes of COVID-19 among communities of color across the state. Essential policies include paid sick leave, expanded unemployment insurance, and enhanced support for food and housing security.[41]

Florida should address the social determinants of health that are hastening the spread and worsening the outcomes of COVID-19 among communities of color across the state.

Lastly, Florida must address long-standing systemic and institutional racism.[42] It can do so over the long-term by investing in communities of color and immigrant communities that have been economically marginalized.[43] In response to the present crisis, the state must invest in the healthcare systems that serve marginalized communities to redress inequities, and must implement wide-spread anti-bias training to ensure that healthcare decisions are never clouded by bias. Doing so is essential to effectively addressing the injustice of healthcare disparities and creating a state that is more resilient to future disasters.

[1] Impacted groups include low-income populations, the uninsured and vulnerable employment groups, such as public transit operators, long-term care facility workers and service industry employees. See Holder C. Address African-American residents’ heightened risks of the coronavirus, Opinion. https://www.miamiherald.com/opinion/op-ed/article241805631.html. Accessed May 1, 2020.

[2] U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States; Florida. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US,FL/PST045219. Accessed April 17, 2020.

[3] Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/. Published March 13, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020.

[4] Gibbons MC. A Historical Overview of Health Disparities and the Potential of eHealth Solutions. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(5). doi:10.2196/jmir.7.5.e50

[5] Disparities. Healthy People 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Disparities.

[6] Racism Laid Bare with COVID-19. Shriver Center on Poverty Law. https://www.povertylaw.org/article/racism-laid-bare-with-covid-19/. Accessed April 17, 2020.

[7] DuBois WEB. The Health and Physique of the Negro American. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):272-276.

[8] For example, as of April 6, 2020, reports have emerged from the District of Columbia where Blacks accounted for 59% of deaths even though they make up just 45% of the total population. The numbers are even more startling in Louisiana where Blacks make up 32% of the total population, but accounted for over 70% of COVID-19 deaths. See, e.g. Artiga S, Garfield R, Orgera K. Communities of Color at Higher Risk for Health and Economic Challenges due to COVID-19. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/communities-of-color-at-higher-risk-for-health-and-economic-challenges-due-to-covid-19/. Published April 7, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020.

[9] Artiga S, Garfield R, Orgera K. Communities of Color at Higher Risk for Health and Economic Challenges due to COVID-19. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/communities-of-color-at-higher-risk-for-health-and-economic-challenges-due-to-covid-19/. Published April 7, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020.

[10] Krogstad J, Gonzalez-Barrera A, Lopez, M. Hispanics more likely than Americans overall to see coronavirus as a major threat to health and finances. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/24/hispanics-more-likely-than-americans-overall-to-see-coronavirus-as-a-major-threat-to-health-and-finances/ Accessed April 18, 2020.

[11] Krogstad J, Gonzalez-Barrera A, Noe-Bustamante L. U.S. Latinos among hardest hit by pay cuts, job losses due to coronavirus. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/03/u-s-latinos-among-hardest-hit-by-pay-cuts-job-losses-due-to-coronavirus/. Accessed April 18, 2020.

[12] Communities of Color at Higher Risk.

[13] Jan T. Two black men say they were kicked out of Walmart for wearing protective masks. Others worry it will happen to them. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/09/masks-racial-profiling-walmart-coronavirus/. Accessed April 17, 2020.

[14] COVID-19 Data Reports. https://www.floridadisaster.org/covid19/covid-19-data-reports/. Accessed April 30, 2020.

[15] COVID-19 Data Reports, and see U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States; Florida.

[16] COVID-19 Data Reports.

[17] For example, in Liberty county, approximately 610 people per 100,000 residents were tested while in Miami-Dade county over 2,700 people per 100,000 residents were tested. See COVID-19 Data Reports.

[18] Salman J, Nichols M. Florida coronavirus testing varies widely, often by income. USA TODAY. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/investigations/2020/04/06/coronavirus-testing-and-income-florida-counties/2933793001/. Published April 16, 2020. Accessed April 18, 2020.

[19] Recht LS Hannah. The Other COVID Risks: How Race, Income, ZIP Code Influence Who Lives Or Dies. Kais Health News. April 2020. https://khn.org/news/covid-south-other-risk-factors-how-race-income-zip-code-influence-who-lives-or-dies/. Accessed May 1, 2020.

[20] U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States; Florida, and see COVID-19 Data Reports.

[21] Dembosky JW, Haviland AM, Haas A, et al. Indirect Estimation of Race/Ethnicity for Survey Respondents Who Do Not Report Race/Ethnicity. Med Care. 2019;57(5):e28-e33. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001011

[22] U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts.

[23] Id.

[24] A note on Florida’s COVID-19 data by race/ethnicity: self-reporting of race and ethnicity is voluntary, over a quarter of individuals in confirmed COVID-19 cases, 4% of hospitalizations and 5% of mortality were of “unknown” race.12 This results in apparent holes in the racial/ethnic data (both state and county level), and gives us a somewhat incomplete picture of emerging disparities. Also, FL-DOH data is broken down by ethnicity within racial groups. We chose, when looking at Blacks, to include all Blacks, but when looking at Whites to only look at non-Hispanic Whites, in recognition of the obstacles to care faced by Blacks of all ethnicities, and Hispanics of all races. Finally, county-level data are reported only by race, not ethnicity.

[25] U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts, and see COVID-19 Data Reports.

[26] COVID-19 Data Reports.

[27] Id.

[28] U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts.

[29] Id.

[30] Health Coverage of Immigrants.

[31] Communities of Color at Higher Risk.

[32] Yager, A. Connecting the Dots: How Medicaid Expansion will Improve Public Health, Increase Financial Stability, and Lessen Disparities in South Florida. Florida Health Justice Project. https://floridahealthjustice.org/connecting-the-dots.html. Accessed April 25, 2020.

[33] COVID-19 Data Reports.

[34] COVID-19 Data Reports.

[35] U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts.

[36] Connecting the Dots.

[37] Health Coverage and Care of Undocumented Immigrants.

[38] The COVID-19 Crisis Is Giving States That Haven’t Expanded Medicaid New Reasons to Reconsider. The Commonwealth Fund. doi:https://doi.org/10.26099/rn45-ee18

[39] Yager A, Harmatz M, Samuels-Staple S. COVID-19 Federal and State Actions. March 18-April 10, 2020: Policy Digest & Recommendations. https://floridahealthjustice.org/uploads/1/1/5/5/115598329/policy_digest_4.30.20.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2020.

[40] Id.

[41] For example, Florida should increase access to paid sick leave by requiring employers with 500 or more employees that are currently exempt under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFRCA) 21 to provide COVID-19 related paid sick leave. In addition Florida should extend unemployment benefits, inclusive of making benefits retroactive to the first day of unemployment. Florida must also enhance rental assistance and forgiveness programs to address the growing crisis of housing insecurity.

[42] For example, the pandemic illustrates the need for outreach and education addressing the fear of wearing a mask in public experienced by people of color with anti-bias messaging aimed at retail and security personnel, as well as public safety officers.

[43] COVID-19: Investing in black lives and livelihoods. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/covid-19-investing-in-black-lives-and-livelihoods